Migration History

The first known immigrant from Japan, Manzo Nagano, arrived in British Columbia in 1877. By 1914, 10,000 people of Japanese ancestry had settled permanently in Canada. The 2016 census reported 121,485 people of Japanese origin in Canada (56,725 single responses and 64,760 multiple responses). The majority of the people of Japanese descent live in three provinces: British Columbia (42 per cent), Ontario (34 per cent) and Alberta (14 per cent).

First Wave (1877‒1928)

The first wave of Japanese immigrants, called Issei (first generation), arrived between 1877 and 1928. Until 1907, almost all immigrants were young men. In 1908, Canada insisted that Japan limit the migration of males to Canada to 400 per year, arranging what was known as the Gentlemen’s Agreement with officials in Japan. As a result, most immigrants thereafter were women joining their husbands or unmarried women engaged to men in Canada. In 1928, Canada further restricted Japanese immigration to 150 persons annually, a quota seldom met. In 1940, immigration ceased after Japan allied itself with Canada’s Second World War enemies, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Japanese immigration did not resume until the mid-1960s, except for family reunifications.

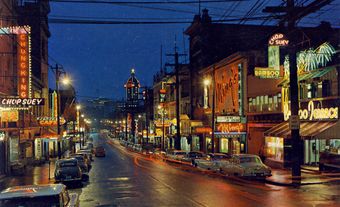

The Issei were usually young and literate. Most were from fishing and farming villages on the southern islands of Kyushu and Honshu; a minority migrated from other parts of Japan. Many settled in the “Japantowns” or suburbs of Vancouver and Victoria, on farms in the Fraser Valley and in fishing villages, and pulp-mill and mining towns along the Pacific coast (see Company Towns). A few hundred settled on farms and in the coal-mining towns of Alberta, near Lethbridge and Edmonton.

Second Wave (1967—)

The second wave of Japanese immigration began in 1967, when immigration laws were amended and a point system was instituted. The point system was based on social and economic characteristics that favoured educated immigrants competent in English or French from industrialized cities. Many Japanese immigrants to Canada during this period worked in business, the service sector and skilled trades.

The 2016 census recorded 45,060 first generation Japanese Canadians (Japanese immigrants); 37,615 second generation (children of Japanese immigrants) and 38,810 third generation and more Japanese Canadians.

A History of Racism and Exclusion

Japanese Canadians, both Issei immigrants and their Canadian-born children, called Nisei (second generation), have faced prejudice and discrimination. Beginning in 1874, BC politicians pandered to White supremacists and passed a series of laws intended to force all Asians to leave Canada. All Asians were denied the right to vote: the Chinese in 1874, Japanese in 1895, and South Asians in 1907. Laws excluded Asians from underground mining, the civil service and professions such as the practice of law, which required the practitioner to be listed on the provincial voting lists. Labour and minimum-wage laws ensured that employers hired Asian Canadians only for menial jobs or farm labour, and paid them at lower pay-rates than Caucasians. When Asians worked harder and longer to earn a living wage, White labour unions accused Asian Canadians of unfair competition, stealing jobs and undermining union efforts to raise the living standards of White workers.

On 7 September 1907, five days ahead of the arrival of SS Monteagle from Punjab — a steamer carrying 901 Sikhs to the CPR pier in Vancouver — hostility toward Asian immigrants erupted. Whipped up by agitators from the Asiatic Exclusion League, a mob of 9,000 smashed windows and destroyed the homes and shops of Asian-Canadians in Chinatown and Japantown. When the mob reached the Japantown section of Vancouver, they were driven away by Japanese immigrants who were veterans of the recent Russo-Japanese war. That success fuelled the “yellow peril” warnings of White supremacists and gave birth to their “big lie” that Japan was smuggling an army into Canada.

During the First World War, with a few rare exceptions, recruitment offices in BC would not accept Asians for military service. To circumvent this practice, over 200 Issei men travelled from British Columbia to Alberta to enlist. Of the 222 who served, 54 were killed. Thirteen Japanese Canadian men received medals for bravery, including Sergeant Masumi Mitsui, recognized for his service at the Battle of Vimy Ridge (see Decorations for Bravery).

After the First World War, discrimination continued. Just before the start of the 1922 salmon season, the federal fisheries department reduced the number of troll licenses issued to Japanese Canadian fishermen by one third. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the BC government denied logging licences to Asians and paid Asians only a fraction of the social assistance paid to Whites.

Community Development

Excluded from Canadian society, Japanese Canadians before the Second World War congregated in enclaves and developed their own social, religious and economic institutions ( see Residential Segregation). In Japantown near the Powell Street Grounds (now Oppenheimer Park) in Vancouver, in Steveston, Mission City and other Fraser Valley villages, and in coastal centres such as Powell River, Tofino and Prince Rupert, Japanese Canadians built Christian churches and Buddhist temples, Japanese language schools and community halls; and, in Steveston, a hospital staffed by Japanese Canadian doctors and nurses trained in Japan and in segregated hospitals in the US. Japanese Canadians formed co-operative associations to market their produce and fish, and community and cultural associations for self-help and social events. By 1941, there were more than 100 clubs and organizations within a tightly knit community of 23,000 individuals, half of whom were children.

In the 1920s and 1930s, even well-educated Nisei who sought employment in business or the professions were unable to obtain employment outside the Japanese Canadian enclaves. Some Nisei had to seek employment in Japan. A few left BC for Ontario. Others started businesses serving Japanese Canadians. For example, BC-born Thomas K. Shoyama , a double Honours graduate from the University of British Columbia, who, after the Second World War, became a senior civil servant in the Saskatchewan and federal governments, started The New Canadian, an English-language newspaper for Japanese Canadians.

Political Activism: Seeking the Vote

Japanese Canadians also organized to challenge their exclusion from the BC voters’ list. Without being on the list, the Nisei and naturalized Japanese Canadians could not vote in federal, provincial or municipal elections, could not practice law or even be on a school board. The franchise (or right to vote) was the key to breaking the discrimination barrier. In 1900, Tomekichi Homma, a naturalized Canadian, launched the first challenge, seeking a court order to have his name entered on the voters’ list. While initially successful when the BC Supreme Court ruled in his favour, he lost when, in 1902, the Privy Council in England ruled that BC had exclusive jurisdiction over its provincial civil rights, and had the ability to exclude persons from the voters’ list.

In the 1920s, the Issei veterans of the First World War, who by their service and casualties had proved their loyalty to Canada, tried again to win the right to vote. Only in 1931, did the BC legislature finally grant the right to vote, but only to surviving Issei veterans.

In 1936 a new Nisei group, the Japanese Canadian Citizens League (JCCL), despairing of gaining the provincial vote, sought instead to gain the federal franchise. While the JCCL delegation was permitted to speak to the Special Committee on Elections and Franchise Acts, the BC Members of Parliament — except Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) members — persuaded the Liberal-dominated Committee to uphold the denial of the franchise. This outcome was not surprising given that the BC federal Liberal campaign slogan in the 1935 federal election had been: “A Vote for ANY CCF Candidate is a VOTE TO GIVE the CHINAMAN and the JAPANESE the same Voting Right that you have!”

During the Second World War, Nisei men tried to follow in the footsteps of the Issei veterans by enlisting in the armed forces. They knew that enlistment would enfranchise not only the soldier but also his wife. Only 32 Nisei succeeded in enlisting before December 1941 when Japan attacked the US base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Most of the 32 were Japanese Albertans and one, Jack Nakamoto of Vancouver, enlisted by travelling east until he persuaded a recruiting officer in Montréal to sign him up. In 1945, the British government requested the right to recruit Japanese Canadians as translators for the British forces. The federal government permitted 119 Nisei men (most of whom had been expelled from their homes in BC and whose families were in detention sites) to enlist as translators in the Canadian Intelligence Corps. The federal government then added a provision to the 1945 Soldiers’ Vote Act disenfranchising any Japanese Canadian who had not previously had the right to vote. Nisei veterans from BC finally got the franchise in 1949 along with all other adult Japanese Canadians.

Expulsion, Detention, Dispossession, Deportation, and Dispersal

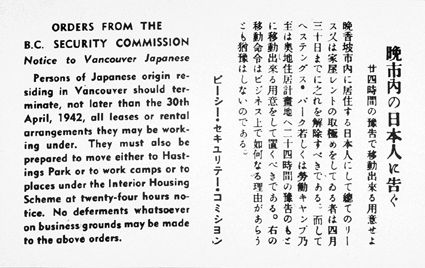

During the Second World War, the federal Cabinet destroyed the Japanese Canadian community in British Columbia. On 25 February 1942, a mere 12 weeks after the 7 December 1941 attack by Japan on Pearl Harbor and Hong Kong, the federal Cabinet, at the instigation of racist BC politicians, used the War Measures Act to order the removal of all Japanese Canadians residing within 160 km of the Pacific coast. At the time the government claimed that Japanese Canadians were being removed for reasons of “national security,” despite the fact that the removal order was opposed by Canada’s senior military and RCMP officers, who stated that Japanese Canadians posed no threat to Canada’s security (see Internment of Japanese Canadians).

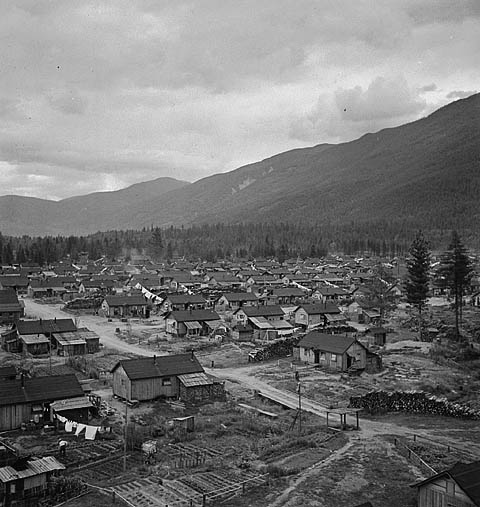

In 1942, 20,881 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry, 75 per cent of whom were Canadian citizens, were removed from their homes, farms and businesses. More than 8,000 were moved through a temporary detention centre at Hastings Park in Vancouver, where the women and children were accommodated in the Livestock Building. The detainees were shipped to camps near Hope, BC, and in the Kootenays, to sugar beet farms in southern Alberta and Manitoba, and to road labour camps along the Hope-Princeton and Yellowhead highways in BC, and at Schreiber, Ontario. Those who resisted the removal of Japanese Canadians were shipped to prisoner of war (POW) camps at Petawawa and Angler in Ontario.

Having physically removed the Japanese Canadians from the coast, the federal government began severing all their ties to BC in preparation for their deportation after the war. Between 1943 and 1946, the federal government sold all Japanese Canadian-owned property — homes, farms, fishing boats, businesses and personal property — and deducted from the proceeds any social assistance received by the owner while confined and unemployed in a detention camp. In 1945, the inmates of the camps, in a biased survey, were forced to choose between deportation to Japan or uncertain dispersal to a location east of the Rocky Mountains. Most chose the latter and were shipped through demobilized POW camps and air bases to Ontario, Québec or the Prairie provinces. In December 1945 — a full year after the US had permitted Japanese Americans to return to their homes on the US Pacific coast — the Canadian government defied Parliament to give the Cabinet the power to deport 10,000 Japanese Canadians to war-ravaged Japan. With freedom of the press restored in January 1946, the deportation plans became general knowledge and produced a massive public protest from all parts of Canada. Referring the matter quickly to the courts to buy time for a political solution, the federal government accelerated the dispersal of Japanese Canadians to provinces east of the Rocky Mountains and expedited the shipment to Japan of 4,000 Japanese Canadians — 2,000 of whom were aging Issei who had lost everything and despaired over starting again, and 1,300 of whom were children under 16 years of age. The remaining 700 were young Nisei over 16 years of age who could not or would not abandon their aging parents.

In 1948, racism as a political tool was finally discredited in BC. First, in an attempt to win two federal by-elections in BC for the Liberals, the federal Cabinet extended the exclusion of Japanese Canadians from the Pacific Coast area for a seventh year. Both Liberal candidates lost to CCF candidates. At the same time, the BC government’s attempt to re-impose a prohibition on Japanese Canadians holding logging licences backfired when forest workers and forestry unions condemned the regulation as “an act of deplorable discrimination.”

On 1 April 1949, Japanese Canadians regained their freedom. The legal restrictions used to control their movements were removed. Ironically, BC had enfranchised Japanese Canadians just one week earlier, thereby removing the legal basis for their discrimination in the province. Although free to return to BC, very few Japanese Canadians had the means or the inclination to move back to British Columbia. (See also Japanese Internment: Banished and Beyond Tears.)

Minoru: Memory of Exile by Michael Fukushima, National Film Board of Canada

Postwar Community

In the 1950s, Japanese Canadians struggled to rebuild their lives but, now scattered across Canada, could not rebuild their communities. The third generation, the Sansei (San-say), born between the 1940s and 1960s, grew up in overwhelmingly White-dominated communities. The remnants of the pre-war Japanese Canadian community persisted only in three newspapers and a few churches, temples and community clubs in the largest cities. Scattered, and without contact during their youth with other Japanese Canadians, many of the Sansei speak English or French but little or no Japanese, and have only limited knowledge of Japanese culture, past or present.

Today, Japanese Canadians work in all occupations, including the service sector, manufacturing, business, teaching, the arts, academia and the professions. The changes since the Second World War are perhaps best illustrated by the fact that more than 75 per cent of the Sansei have married non-Japanese.

Lobbying for Redress

In the late 1970s and 1980s, redress of the wrongs suffered during the Second World War became the primary focus of a revived national organization for Japanese Canadians, the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC). The opportunity came following the publication of the novel Obasan (1981) by Joy Kogawa, and of new histories that used the federal government’s own documents. The first piqued public interest in the wartime experiences of Japanese Canadians while the latter gave the NAJC the facts it needed to persuade the federal government to acknowledge wartime wrongs, to negotiate compensation for those who were wronged and, most importantly, to change Canada’s laws to prevent other Canadians from suffering similar wrongs.

The redress campaign initially divided Japanese Canadians. A small group, centred in Toronto, wanted to accept a group settlement of $6 million offered in 1984 by the Conservative government. They viewed this settlement as politically realistic and, haunted by memories of their wartime experiences, feared retaliation against Japanese Canadians by the government if they demanded more. A second, nationally-representative group, led by NAJC President Art Miki, viewed the $6 million as a token offer and a continuation of the wartime attitude that Japanese Canadians could be treated as an amorphous group on whom a settlement could be imposed.

To the leaders of the NAJC, a just process was as important as achieving redress. They wanted a negotiated, not an imposed, settlement and a monetary acknowledgement that their individual rights had been abused. Between 1984 and 1988, the NAJC held seminars, house meetings and conferences; lobbied and petitioned the government; sought the support of First Nations, ethnic, religious and human rights groups; and composed and distributed studies and press materials designed to educate politicians, Japanese Canadians and the general public. One study by Price Waterhouse, a respected accounting firm, revealed that the economic losses from the wartime property confiscation were $443 million in 1986 dollars. By 1986, national polls showed that 63 per cent of Canadians supported redress of some kind and 45 per cent supported individual compensation.

Negotiations with the NAJC

By the spring of 1988, the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney was almost ready to negotiate. The Emergencies Act, a replacement for the War Measures Act, was making its way through Parliament. On 14 April, the NAJC held a well-publicized redress rally on Parliament Hill that resulted in a groundswell of support by the Canadian public that could no longer be ignored. Then, on 20 April, the United States Senate approved a redress package for Japanese Americans that included individual compensation of $20,000. By mid-June, tentative negotiations began with Minister of State for Multiculturalism Gerry Weiner, but they seemed to stall. A meeting called for July was cancelled without explanation.

On 21 July, the Emergencies Act became law, abolishing the War Measures Act and putting in place an emergency regime for Canada that expressly prohibits discriminatory emergency orders, permits Parliament to override the emergency orders of the government, requires an inquiry into the actions of the government after any emergency, and provides for payment of compensation to the victims of government actions. It has never been used. The first goal of the redress campaign had been achieved.

On 10 August, US President Ronald Reagan signed the US redress package into law and the NAJC began planning a second demonstration on Parliament Hill. The demonstration proved unnecessary. On 25 August, negotiations resumed in Montréal, but not with the multicultural minister. This time the negotiator was Secretary of State Lucien Bouchard, a far more powerful minister. Two days later, after 17 hours of negotiation, the NAJC agreed to a redress package.

On 22 September 1988, Mulroney rose in the House of Commons to acknowledge the wartime wrongs and to announce compensation of:

- $21,000 for each individual Japanese Canadian who had been either expelled from the coast in 1942 or was alive in Canada before 1 April 1949 and remained alive at the time of the signing of the agreement;

- a community fund of $12 million to rebuild the infrastructure of the destroyed communities;

- pardons for those wrongfully convicted of disobeying orders under the War Measures Act;

- acknowledgement of the Canadian citizenship of those wrongfully deported to Japan and their descendants; and

- funding of $24 million for a Canadian Race Relations Foundation. civil rights projects, programs and conferences.

In 2012, the government of British Columbia apologized to Japanese Canadians for its role in their internment and dispossession. Naomi Yamamoto, the first Japanese Canadian elected to the BC legislature, whose father was interned during the Second World War, introduced the motion. Vancouver City Council apologized the following year. In 1942, city council had passed a motion calling for “the removal of the enemy alien population from the Pacific coast to central parts of Canada.”

Japanese Canadian Historic Sites

There are only a handful of sites on the Canadian Register of Historic Places that are significant to Japanese Canadian history, most of which are located in British Columbia. They include the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre in New Denver, the Langham Cultural Centre in Kaslo, the Martial Arts Centre in Richmond and three buildings where Japanese immigrants boarded in Vancouver’s former Japantown (see Historic Site).

In July 2016, Heritage BC announced the Japanese Canadian Historic Places Recognition Project. The project sought to recognize places in British Columbia that are significant to Japanese Canadian history. The nomination process was open to the public, which suggested 176 sites. In April 2017, 56 of those sites were officially recognized by the province and pinned to an interactive map created by Heritage BC. The map also includes the sites that were nominated.

The map depicts significant streets, neighbourhoods, parks, memorials and historic buildings, among other historic markers throughout the province. It also outlines the “protected area,” stretching 160 km inland from the Pacific coast — an area that Japanese Canadians were ordered to vacate during the war. Many of the sites are related to internment, including road labour camps in Hope-Princeton and Yellowhead-Blue River and internment camps in the Slocan Valley (including Lemon Creek, Popoff and Bay Farm). Other sites memorialize Japanese Canadian businesses such as the Deep Bay Logging Company, Buddhist temples, Japanese language schools, gardens and more.

Community Centres and Associations

The National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) is a national collective of locally-based Japanese Canadian organizations. The NAJC is a non-profit community organization that was first formed as the Japanese Canadian Citizens Association in 1947. The NAJC focuses on human rights, community development and government relations.

During the redress campaign, other Japanese Canadian cultural centres or associations emerged in Montréal, Winnipeg, Vancouver, Victoria, Edmonton, Calgary, Lethbridge, Ottawa, Regina and Thunder Bay. Several martial arts and kendo clubs, and taiko groups operate across the country, including in Halifax.

Several organizations across Canada promote Japanese heritage and Japanese Canadian community life, such as Toronto’s Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC). Founded in 1963, the JCCC offers programs ranging from tea ceremony initiation and the art of calligraphy to martial arts and Japanese business etiquette. The JCCC also hosts several events each year, including spring and summer festivals. Similarly in Burnaby, BC, the mission of the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre is to preserve and promote Japanese Canadian history, arts and culture through programs and exhibits that connect generations and inspire diverse audiences.

Asahi Baseball Team

In the face of prejudice and persecution, sports offered a path to dignity and courage. While Japanese Canadians participated in various sports, from judo to bowling, baseball had a special place in the hearts and minds of prewar community members.

Before the Second World War, the Asahi baseball team was legendary in Vancouver. The club was established in 1914 and was one of the city’s most dominant amateur teams, winning multiple league titles in Vancouver and along the Northwest Coast. The Asahi stayed at the top of the Pacific Northwest Japanese Baseball Championship for five consecutive years (1937–41), and earned applause across colour lines. When every Japanese Canadian was confined in detention camps during the Second World War, the former Asahi players played a leading role in creating baseball diamonds in the camps (see Vancouver Asahi).

The unique skills of the Asahi were recognized in 2003, when the team was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and into the British Columbia Sports Hall of Fame in 2005. A commemorative plaque was unveiled in 2011 in their home field, the Powell Street Grounds, the heart of Japantown in Vancouver.

Japanese Canadian Culture

Culture changes over time. Although immigrants from the first wave, the Issei, practised many traditional Japanese skills such as martial arts, odori, origami and ikebana, they learned them in the Meiji and Taisho eras of their youth. The destruction of their communities in the 1940s reduced their opportunities to practise these skills and to use the Japanese language. While the Nisei went to Japanese language schools in the 1930s, their children and grandchildren had few opportunities to learn Japanese language or cultural traditions.

The language and cultural traditions of the post-1967 immigrants, the Shin Ijusha, are different from those of the Issei in the same way that Victorian English and manners are different from modern English culture. The culture of the post-1967 immigrants reflects changes in Japan over the last century. They bring to Canada their knowledge of both ancestral cultural skills and of contemporary Japanese language, literature and art, including popular art forms such as anime and manga. In the 2011 NHS, 40,180 people reported Japanese as their mother tongue (first language learned).

Japanese Canadians, now into the fifth generation (Gosei), have developed new and hybrid forms of culture and art. For example, taiko drumming groups are found in many Canadian cities. Canadians of Japanese ancestry are diverse in their cultural practices, experiences, education and economic circumstances.

Prominent Japanese Canadians

Well-known Japanese Canadians include novelists Kerri Sakamoto, Aki Shimazaki, Michelle Sagara, Hiromi Goto, Kim Moritsugu and Joy Kogawa, poet Roy Miki, writer Ken Adachi, filmmakers Midi Onodera and Linda Ohama, scientist David Suzuki, public servant Thomas Shoyama, architects Raymond Moriyama and Bruce Kuwabara, community leader Art Miki and agriculturalist Zenichi Shimbashi. Artists include Takao Tanabe, Miyuki Tanobe, Roy Kiyooka and Kazuo Nakamura. Musicians include Jon Kimura Parker and Jamie Parker.

Politicians include Bev Oda, the first Japanese Canadian Member of Parliament and federal cabinet minister, BC Liberal cabinet minister Naomi Yamamoto and former Ontario Progressive Conservative Cabinet minister David Tsubouchi.

Athletes include judoka Mas Takahashi and hockey player Vicky Sunohara, who was part of the national women’s hockey team that won silver (1998) and gold (2002, 2006) at the Olympic Winter Games, as well as Devin Setoguchi of the Minnesota Wild (NHL) and AHL players Jon Matsumoto and Raymond Sawada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom